This is an article I wrote for Reading Matters, the in-shop newsletter published by Bookazine.

HERE IS THE GOOD NEWS: Hong Kong has a thriving industry of independent publishers. Here is even better news: this is not London or New York, and most (if not all) presses are happy to receive manuscripts directly from authors. So, assuming you’ve written a great book, you don’t necessarily need a literary agent to get published.

HERE IS THE GOOD NEWS: Hong Kong has a thriving industry of independent publishers. Here is even better news: this is not London or New York, and most (if not all) presses are happy to receive manuscripts directly from authors. So, assuming you’ve written a great book, you don’t necessarily need a literary agent to get published.

These ideas should help you get started.

First, find a suitable publisher to submit your manuscript to. Here’s an obvious but often overlooked tip: choose a publisher which already publishes works in subject areas similar to yours. They will be more adept at promoting your book, and the editors there are more likely to take a personal interest in it.

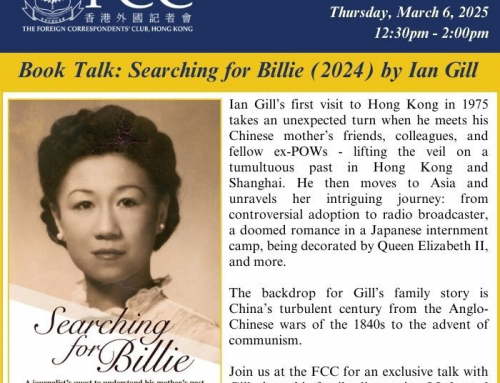

You can do your research online; many publishers’ submissions guidelines can be found on their websites, or in annual directories. Or simply walk into your local bookshop and browse the shelves for titles similar to yours, and note who publishes them.

It is a fact that many publishers are overwhelmed with submissions from prospective authors, and if your proposal is vague, poorly presented or inappropriate, it will be consigned to the ‘slush pile’ to be read at a later date – or maybe never. Only a tiny proportion of the manuscripts sent to publishers each year get published by them. To make sure yours is one of the few, you should craft a proposal which grabs the attention of the reader, states your concept clearly, and provides all the necessary information in one place.

Write a covering letter or email, indicating who you are, what kind of book you have written, and why this publisher should be interested in it. If you can, compare it to similar books on the market which have done well. Your aim is to convince the editor of two things: that this book is a winner which will sell, and that you are an outgoing author who is able and willing to assist in making it a success.

Include a one-page summary of the book, and two or three sample chapters or illustrations. If you tick all the boxes in this way, your proposal is likely to go straight to the head of the queue. Good luck!

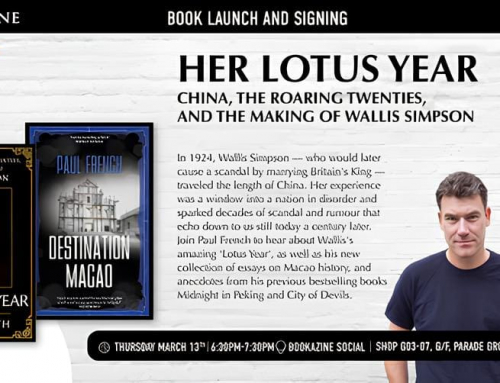

Publishing contracts vary, but in most cases they will set out that the publisher is granted a licence to publish the work, at its own expense, and will pay you royalties on sales. Royalties may be expressed as a percentage of monies received from sales, or as the number of copies sold multiplied by a percentage of cover price (and these are not the same, as retailers and distributors take their cuts before the proceeds of sales reach the publisher). Some publishers may pay the author an advance on royalties, but this is not especially common among small presses with limited resources. Most will require the author to co-operate in promoting the book as widely as possible. (If you are a shrinking violet, this may be the perfect opportunity to conquer your fear of public speaking).

Finally, a word of warning: If a publisher asks you to pay production costs, or asks you to commit to buying quantities of your own book, then you are probably dealing with a vanity or subsidy press (although they won’t call themselves this, often describing their model falsely as “self-publishing”). If a publisher has not invested its own money in the book, and has already made money from you, then it has little incentive to distribute or sell the book. For more advice see “Guidance on Vanity Publishing” at the Society of Authors website (and there is plenty more good advice there too).

If you absolutely cannot find a commercial publisher to take on your work, then you are better off genuinely self-publishing it. There are various ways to do this – either by engaging a printer to run off copies, or by using an online service like Smashwords, Blurb or Kindle – and although the marketing and distribution are your responsibility, at least you retain control over the process.

Pete Spurrier runs Blacksmith Books, a Hong Kong publishing house.

This is good information. Thanks for the tips. I might be in touch with Blacksmith in the near future for a photographer friend of mine who might be needing some publishing done. I am acting on his behalf in Germany, and am his main promoter these days.

The information that was provided is very helpfull, I will contacting you folks in a day or so about my book.

Respectfully Sam Pizzo

Nowadays, publishing a book of pictures in color is still rather expensive. I find that very few publishers are interested in publishing coffee table books. On the other hand, books on doing business in Asia are still popular and have a market in USA.

You are right, Frankie. We were very lucky that “China: Portrait of a People”, a photo book by Tom Carter (http://www.blacksmithbooks.com/9789889979942.htm), struck a chord in the US, UK and Canada. If it hadn’t done well, we wouldn’t have done any others, as ful-colour printing is a big investment.

Nowadays, coffee table books are too expensive to produce. Even docotrs’ waiting rooms don’t stock them. Even in public libraries, these books are a headache to stock. I can’t imagine H K has a big market for them for space reason alone. Young people read everything on line any way.

you really feel sad when you go to book sales to see those colorful and expensive coffee-table books sold for $1 each copy. Almost an insult to those photographers who are so experienced and talented.

Space is a premium these days, even in spacious USA, not to mention Hong Kong. I just attended a meeting with university librarians. They would rather not accept any donated books, unless a precious copy.

I wrote a foreword in a book published in English by a friend. It was published by a regional publisher (not in H K, but in Singapore). I am helping him to market his book in North America. I was shocked to have known that so little was done by his publisher in Asia in promoting his book outside the region. Hardly any advance copies were sent to reviewders in known publications to write reviews.

Hi Frankie, did the publisher have distribution in North America? If not, and the book couldn’t be bought there, then there may have been no logic in sending out lots of advance copies.

I am not talking about a mass market for best sellers. The book is sold by Amazon. As you well know, for a book to attract readers, you need book reviews, flyers, promotions on the internet, not to mention book tours. I am sending complimentary copies to magazines, and Asian studies libraries etc. Not much one can do if the publisher does not take an active part.

I quite agree, all this needs to be done. If the publisher doesn’t do this, there are two possibilities: 1. it is incompetent and it will go out of business, or 2. it is a vanity press which has already made its money by charging the author.

Where can I find the email address to send my query? Many thanks in advance for any hint.

All here, Pearl: http://www.blacksmithbooks.com/submissions.htm Thanks.

I would like to find a publisher for my children’s books

in Hong Kong or china.

I am an established author in England of thrillers but I also write

children’s book as well. My publisher does not do children’s books.

Malcolm

I am looking for a publisher/printer for my fully illustrated children’s book. It is formatted as an 8″x10″ hardcover with jacket and the full-color illustrations are professionally painted by a children’s book illustrator. I just need the publisher, the ISBN and an affordable price. I am American but live in Shanghai. I hope to visit International schools and sell oodles of books so that I can sleep on a mattress stuffed with gobs of money. Does anyone have any recommendations?

Book publishing is a treacherous endeavor. If you are famous like Michelle Obama, her memoir sells 1.4 million copies in the first week. If you are an obscure author writing on an exotic subject, you are lucky if you can sell 50 copies.