Fred Schneiter, author of The Taste of Old Hong Kong, has many food-related tales to tell from his 30 years on the China coast…

THE BEST RIBS IN TOWN

One of the most momentous events in the history of Hong Kong occurred in 1984 when British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher called on Beijing to discuss the 1997 expiration of Britain’s 99-year lease on the New Territories, a buffer area which lay between China and Hong Kong.

Hong Kong business interests–largely the ones with ties to Britain–had actively encouraged the dialogue, hoping an extension of the lease could be negotiated. Without it, the little enclave’s boundaries would be pushed back, deep into the city, reducing British Hong Kong to little more than a hangnail on the long arm of China.

To the surprise of those who didn’t fully grasp how the Chinese had always felt about what they called “the three unequal treaties” on which British Hong Kong was based, Beijing cordially advised Mrs. Thatcher that China was taking back the New Territories.

Oh, and by the way, the rest of Hong Kong as well.

Oh, and by the way, the rest of Hong Kong as well.

Faced with the geopolitical realities, Britannia waived the rules and went along with the Chinese position, in spite of the fact it ran contrary to the British view that Hong Kong had been granted to Britain “in perpetuity.”

The Queen’s best diplomatic and political minds and her capable cadre of Old China Hands had anguished and reflected long and hard for an answer as to how Britain might get a better deal. But it proved a Chinese question for which there was no British answer. Sometimes the dragon wins. And rather like Humpty Dumpty, all the queen’s horses and all the queen’s men couldn’t put British Hong Kong back together again.

Allowing even for the Chinese propensity for patience, many found it curious that the People’s Republic didnt simply send out engraved invitations announcing they would hold a reception in Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel at noon Tuesday to take back the whole of Hong Kong. Over a span of nearly 50 years, since the establishment of the People’s Republic, China had never recognized the old post-Opium Wars treaties anyway. To them, these Hong Kong treaties simply didn’t exist.

With the curtain slowly descending on British Hong Kong, despite the uncertainties and apprehensions in the years leading up to the 1997 deadline, resilient Hong Kong held its position as one of most dynamic and envied economies in the world. There were changes taking place, of course, and one of the most subtle was a quiet demographic one, with young scrubbed well-educated people, mainly in their twenties, moving in from America, the United Kingdom and elsewhere to fill a void created by the departure of young Hong Kong Chinese who had taken leave, to return later with a passport which afforded the family an emergency “parachute.” Hong Kong had traditionally been a senior posting for International Old Boys. Any Western young adults were almost sure to be kids home from college for the holidays. Now, young Westerners were coming on their own, in pursuit of Hong Kong’s golden dragon of opportunity.

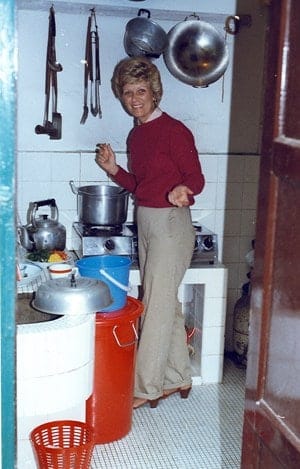

A couple members of this new breed would typically start out sharing one of Hong Kong’s US$1,000-a-month, old, modest and cramped walk-up flats next to a noisy freeway on a little side street with a kitchen not much larger than a bathtub. Dinner typically was taken standing in front of a wheezy little old refrigerator, beneath a dim bulb which dangled from a cord from the ceiling. But they had caught the scent of the dragon and it was not unusual for those who held to it a few years–and caught its tail–to do very well indeed.

It was a particularly fortuitous era. At its height, daughters Heidi and Lesli met and married handsome, ambitious and promising young Americans, Oliver Silsby and Jerry Hammerschmidt, with The Lovely Charlene and I eventually acquiring eight more grandchildren, all born in historic Matilda Hospital on Victoria Peak, high above Hong Kong. The sons-in-law, both in the investment field, would later observe that they could have saved money if–when they first got married–they had simply built a wing on the hospital’s maternity ward.

It was a particularly fortuitous era. At its height, daughters Heidi and Lesli met and married handsome, ambitious and promising young Americans, Oliver Silsby and Jerry Hammerschmidt, with The Lovely Charlene and I eventually acquiring eight more grandchildren, all born in historic Matilda Hospital on Victoria Peak, high above Hong Kong. The sons-in-law, both in the investment field, would later observe that they could have saved money if–when they first got married–they had simply built a wing on the hospital’s maternity ward.

Among this young breed of entrepreneurs were some who opened night spots and eateries, catering to Hong Kong’s new, upbeat international customers. Among the more trendy and popular places were those which featured pork spareribs. Smart marketing, as ribs are popular in many cultures in both Asia and the West.

However, the question of how best to prepare ribs has caused as much impassioned debate among aficionados as chili recipes inspire among followers of that inclination. It can be argued that some of the best ribs are prepared by the Chinese, who’ve likely been eating them since long before anybody else figured out how to catch and cook a pig.

In the early 1990s, Hong Kong’s Sunday Morning Post Magazine sponsored “The Great Rib Round Up” to establish where “the best ribs in town” could be found.

Reporting on the surprising results of the contest, the article suggested that “not since Adam and Eve has a rib caused such controversy.” It went on to speculate that the outcome “perhaps hinted at something most of us have always suspected about connoisseurship.”

What happened was, the panel of international food experts, after a blind taste test, bypassed Hong Kong’s most highly-hyped and trendy rib restaurants and awarded top honors to a rack of fast food shop ribs which had been slipped into the competition as a joke. The magazine noted the winning ribs sold for “about a quarter of the price of any of the other contenders and are served with one tenth the fuss.” Lead Judge Martin Yan, international television chef and food writer, observed with refreshing Chinese pragmatism, “Oh well, it’s only a bit of fun, hey.”

The winning ribs came from Maxim’s Food Group which, at the time, was operating from nearly 300 locations throughout Hong Kong. This included 53 Chinese restaurants (some of palatial opulence), 18 European restaurants, 118 cake shops and 77 fast food and express outlets. Maxim’s was serving some 320,000 people every day.

Maxim’s Senior Manager Pierre Tang, a longtime friend and one of Hong Kong’s most accommodating gentlemen, understandably stopped short of sharing his rib recipe, but, when asked, confirmed that the following guesstimate affords us a close shot at it…

CHINESE PORK SPARERIBS

Serves 4

Marinade:

1 teaspoon garlic, peeled and minced or passed through a garlic press

1 teaspoon fresh ginger, peeled and minced or grated

1 Tablespoon Shao Xing wine or good dry sherry

3 Tablespoons honey

3 Tablespoons hoisin sauce

1 Tablespoon black bean garlic sauce

2 Tablespoons regular soy sauce

1 teaspoon five spice powder

1 Tablespoon sugar

Ingredient:

Baby back pork rib bones, 5 or 6 for person. Have the butcher cut the rack in half lengthwise. Rinse and dry with paper towels. When cooked and ready to serve, slice racks into individual bones.

Glaze:

3 Tablespoons honey

2 Tablespoons hot water

Retained marinade

Combine marinade ingredients in a medium bowl, mix well and pour into large sealable plastic bag. Place ribs in the plastic bag, eliminating as much air as possible. Swirl bag to coat ribs evenly. Marinate at room temperature for 3 hours or in the refrigerator up to 8 hours, swirling bag occasionally. Preheat oven to 425F. Partially fill baking pan 1/3 full with hot water. Place oiled wire baking rack over pan. Remove ribs from plastic bag, retaining marinade, and place ribs on oiled baking rack with space between pieces. Pour marinade into a medium bowl and mix well with glaze ingredients and set aside. Place pan with the ribs in oven on lowest rack. Bake about 10 minutes. Baste glaze on ribs. Turn ribs over, baste and bake about 10 more minutes. Check water level and add more hot water if pan is boiling dry. Baste. Turn and baste and bake about 8 to 10 more minutes. Check for doneness with a test slice between bones. Juice should run clean. Move pan with ribs to upper rack 6 inches under broiler and broil about 2 minutes. Remove ribs from oven, immediately slice into individual pieces. Place on serving dish and serve hot.

Well worth the effort, this great recipe–from China Hand and longtime friend and former neighbor Marda Stoliar–does involve a bit of work. However, if you are inclined toward an outdoor BBQ version of these cut-in-half ribs, here’s how:

Prepare marinade, retaining 4 tablespoons for basting on the grill later. Marinate the ribs 2-3 hours. Preheat oven to 225F. Lightly oil a baking pan and line with aluminum foil for easier cleanup. Remove ribs from marinade and place ribs in the oiled and foiled pan and cover pan lightly with a sheet of aluminum foil. Discard the used, saving the unused, marinade. Place ribs in the middle of the preheated oven, 2 hours. With the leftover unused marinade, prepare the glaze recipe. After the 2 hours in the oven, remove ribs, place on heated BBQ grill and baste the marinade on the ribs on the BBQ grill, 5 minutes on each side on medium heat. Remove ribs from grill and slice into individual pieces between bones before serving. Juice should run clear, indicating ribs are done.

An excellent main dish, just a few ribs are well-suited as a side dish in a Chinese meal. In ordering, keep in mind that ”ribs” to a butcher tends to come across as a rack or a slab or a side of ribs so be sure the butcher understands that you want just a few bones. In eating these BBQ ribs as part of a Chinese dinner, you can pluck these off the serving plate with a serving spoon or chopsticks. This is of those things best eaten with the fingers. Provide diners with a chilled or partially frozen moist washcloth. Also provide a bowl for bones. A bowl of warm black tea with a few thin slices of lemon may also be provided to clean and freshen fingers after eating. You’ll find a ginger grater at an Asian market or a kitchen specialty shop. Ginger is stringy and when grating, little stringy nests may gather which should be removed with a toothpick and discarded.

Shao Xing wine, Xing pronounced Shing, will be found in a well-stocked Asian market. Warmed, it is served as a dinner wine in a cordial glass or a sake cup. If you find it labeled “cooking wine” it has had one and a half percent salt added so keep that in mind when adding salt to a recipe. Unsalted Shao Xing is well worth the search. Amber colored raw turbinado sugar which you should find at the supermarket in crystal form is recommended. This is similar to what the Chinese use and call rock “sugar” or rock “candy.” In Chinese the word translates either way. You’ll find the Asian ingredients called for in Asian markets or in the Asian section of your supermarket.

More recipes? See here.

Leave a reply