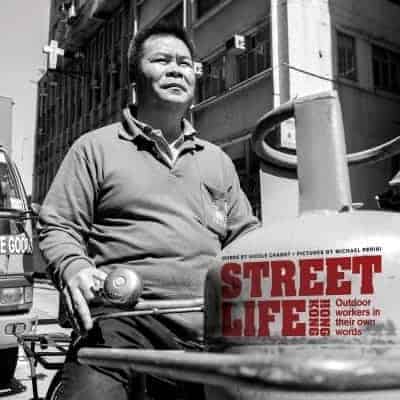

In this excerpt from Street Life Hong Kong, Aberdeen harbour fisherman Kwok Shu-Tai talks about his life and work in his own words. The interviews in the book were carried out by Nicole Chabot and are accompanied by photographs from Michael Perini.

I KNOW EVERYBODY IN ABERDEEN and everybody here knows me. They call me by a nickname – ‘Ah-Q’, after the character in the old TV series, ‘The True Story of Ah-Q’… It’s a funny story: my hair was very thin back then and someone told me that if I cut it, it’d grow back thicker. My older brother began cutting my hair, but, part of the way through, I changed my mind, which left me with bald patches. My new ‘do’ made me look a lot like Ah-Q, and I’ve been called the name ever since.

Like a fish to water

Like a fish to water

I’ve been a fisherman since I was a child, and all the generations that I’ve known have been fishermen too. In fact, I was born on a boat and used to live on the water, though we went to a primary school on land.

During the school holidays, we’d swim to the rocks and catch oysters and sea snails to eat; and we’d also fish. After primary school, I didn’t study any more. I was apprenticed by my father, and when I was of age, I took the boat exams to get my licence, which allows you to operate many different types of vessels. You also need to have boat licences for Hong Kong and the Mainland, and there’s a ‘mass fishing licence’ which you need to catch fish.

After you marry, you have to have a place to live – you don’t want to have your wife and children living on a boat, right? Actually, in my case, even before I was married, I had a home on land, though I mostly slept on the boat. My wife used to live on the water in a boathouse like me, because her mother and father were fishermen as well. Even today, I prefer being on the boat because I’m used to it. If I’m ashore, I never turn on the air conditioning.

This is a fishing boat, and it’s co-owned between the ‘brothers’. We had it made in the Mainland four years ago, simply by giving the dimensions we wanted to the shipyard. We share the labour. I drive the boat; my brothers cast and pull the net; and, in the Mainland, we have another five workers.

The Mainlanders are responsible for the nets. We pick them up from Lingding Island [in the Pearl River estuary in Guangdong], and, while there’s no rule about how long they stay, they usually go home for festivals and holidays. Right now, it’s Mid-Autumn Festival so they’re back home. Once it’s over, they’ll come back out. For Chinese New Year, they go home for longer. When they’re away from home, they live on the boat.

Mapping the schedule

Most of the time, we stay close to the shore to fish. This could mean a day trip, or sailing just outside this bay in Aberdeen, but sometimes we’re more flexible and go for two or three days, depending on the destination. If we go to places nearby, such as Po Toi Island [3 km off the southeastern tip of Hong Kong], then we leave at 4 p.m. and return the next day. If we go further, it could take seven to eight hours just to get out there, so we stay away for two to three days.

How often we go depends on the weather and season. In the summer, we go out more – it’s less windy; and unless there’s a typhoon, we go out most of the time. In the winter, it’s quite windy… It depends on the geography as well. Certain areas are less windy and have a greater yield. If there’s likely to be only a low yield, we won’t go out…

Mahjong is a very popular form of entertainment which is used to kill time. In the past, people would round up and play pai kau [a group game played with domino pieces with a minimum of two people] in the holidays; but my generation doesn’t gamble any more because it hurts morale. On land, we play football; and, in the summer, we dragon boat. I used to win a lot of awards for dragon boating. I’ve represented Hong Kong three times at international dragon boat competitions, though my athletic prime has now passed.

Catch of the day

Catch of the day

In the past, we would lure the fish to the side of the boat with our lights, but, over the past 20 years, we’ve been detecting them with radars. We mostly catch fish, and the catches are seasonal.

Right now, we’re starting to catch Yellow Croaker and Lion Head Croaker. In the summertime, we catch squid, and other fish. The biggest fish I’ve ever caught was about 260 catties heavy [286 lbs]. It was a kind of mackerel. In Sai Kung seafood restaurants, you can see plenty of big fish on display, mackerel included. There are a few different mackerel species, and the biggest can weigh as much as 300 catties [330 lbs].

After we catch the fish, we put them on ice, though this depends on the type of fish, because the smaller the fish the quicker it spoils, which means we need to sell them the next morning. We can keep larger fish for longer. We sell the fish to vendors we know.

There are a lot of products related to the sea such as oyster sauce and shrimp paste, but we don’t play a role in making them. We do catch oysters, but we won’t make them into sauce. As for shrimp paste, my mother used to make it… She’d sun-dry the shrimps for at least 10 days, and then grind them into a paste using a mortar and pestle…

Leaps of faith

I’m a little different from most fishermen in Hong Kong, because I’m a Christian. In fact, the past few generations of my family have all been Christians, which is quite rare for fishermen here. Usually, they worship Tin Hau [the goddess of the sea] or their ancestors.

Hong Kong fishermen usually have a lot of superstitions, whereas Christians have few. For example, in baak si [‘white events’, or deaths], when someone’s family member dies, a Tin Hau or ancestor worshipper won’t let family members of the deceased onto their boat.

Also, although we’re supposed to eat fish at Chinese New Year, because it’s said to encourage a surplus of food, which is auspicious [nihn nihn yau yu, a saying which translates as ‘having fish every year’], we don’t just eat it at New Year; we eat it all the time.

Other superstitions about fish…? Everyone used to have smaller boats, and fish would sometimes leap aboard out of the water. This is known as ‘dragon headed carp’. Legend has it that carps become dragons after jumping through the ‘dragon’s gate’ at the top of a river, and is considered very lucky. However, if you catch one of the fish, then the saying ‘pick up a dragon carp, and a man will die’ applies. We’ve never had this unlucky situation happen before.

Beliefs are an individual choice, and people don’t hold our faith against us. In fact, we Christians are quite popular! I have a cross here [points below the windscreen on the other side of his boat], and a bible in my room, but I seldom go to church as it’s hard to find time on Sundays. Sometimes we’ve taken the boat out, you see, and are not always back in time for the service. Faith is a strange thing – some people are more devoted, and others less so.

Making waves

Making waves

You have to be able to swim to be a fisherman, and you have to have a good memory, because you need to know which fish to catch each season, and which types of nets to use.

I’m not afraid of the water, but in the typhoons of the past, living on a boat could be extremely scary. The boats were small – nowadays they’re much bigger – and back then, the typhoons were a lot more powerful because there weren’t as many tall buildings. The youngsters would take safety ashore, while the adults would stay on the boats, anchoring them down.

But, the scariest thing I’ve ever experienced at sea? Once, a fishing net got stuck in the engine of the boat, and I had to dive underneath the boat to cut the net. The waves were strong, and it was hard to tell where the boat was moving. When I surfaced, I was hit by the boat. It was a minor injury, but if I’d been hit on the head, I might have fainted. I wouldn’t have died, though; I had my ‘brothers’ up on the boat, and had taken safety precautions – I was tied to a rope, and had scuba gear on with a tank of air.

Another challenge to fishermen used to be land people’s discrimination towards us, here in Ap Lei Chau. People on the land would call us ‘Tanka’; and the Tanka were considered a lower class. Today, though, everyone’s culture is more alike, and being a fisherman is considered to be just another profession. Boat people and land people are the same. The relationship depends on how you carry yourself. If you’re always angry and hateful, then no one’s going to like you, but if you’re jovial, you’ll have friends…

What’s most dangerous at sea is a tired person. If you’re driving a boat and you’re tired, it’s easy to crash. The Lamma Island boat incident was a catastrophe… For driving, we comply with the British standard, whereas at sea we use the international standard. In the Lamma disaster, the boat which hit the other boat should have given way. In my view, and from my experience, the boat that was hit was in the right, while the one that hit it was in the wrong.

End of a lifestyle

Aberdeen is a famous place in terms of boats and fishing, but in the last few decades, lots of high-storey buildings have been built and there are fewer shipyards. It’s less scenic now, because they keep on landfilling and narrowing the bay.

In the past, there were spots that were very beautiful. There weren’t so many buildings and there were streams that would run down from the mountains, which you could drink from. Now, you don’t dare drink it, and there’s much more flotsam and plastic bags on the water… There’s so much packaging these days. If people are disciplined, they throw their rubbish in the bins, but if not, they throw it in the sea.

In the past, there were spots that were very beautiful. There weren’t so many buildings and there were streams that would run down from the mountains, which you could drink from. Now, you don’t dare drink it, and there’s much more flotsam and plastic bags on the water… There’s so much packaging these days. If people are disciplined, they throw their rubbish in the bins, but if not, they throw it in the sea.

As for human waste, we have a really nice toilet downstairs, but the waste is actually drained out to sea. Bodily waste doesn’t at all affect the sea, because it’s bio-degradable and eaten by small fish – in fact, I often swim in the water, especially in the summer. Pollution-wise, most comes from the Mainland. The waters in the southwest are polluted because of the rubbish in China, and it’s the same with the air pollution as well.

Hong Kong’s fishing culture is disappearing, and after my generation it’ll be gone, because there won’t be anyone to take the lead. I come from a long line of fishermen, but am not sad to see it go. I would never wish my children to be fishermen, because it’s a difficult life.

Having said that, though, there are plenty of good things about this life, like the better air quality compared to people who work indoors. At our workplace out at sea, there isn’t much dust. There are also the sunrises and sunsets, which are beautiful out on the water, though we’re a little desensitised because we’re so used to seeing them. I’m actually very satisfied with the life that I lead.

Read more stories in the book.

Really a very interesting story. It is the real story of the fisherman Kwok Shu-Tai. Maximum days of his he spent on the water really it is very interesting thanks for such a wonderful and interesting story.