In this excerpted chapter from Hong Kong Confidential, author David T. K. Wong recounts his time as Hong Kong’s deputy postmaster general in 1980, and explains what scheme Special Branch were operating in the basement of the GPO.

Chapter 16

The Q List

When I was installed as the Deputy Postmaster General at the General Post Office at Connaught Place at the beginning of 1980, I was delighted to find myself in an office with a marvellous view of the harbour. The building had been completed only in August of 1976, as the colony’s fourth General Post Office. It was on a prime harbour-front site that was worth a fortune, a mere stone’s throw from the Star Ferry Pier.

The previous General Post Office, opened in 1911, had been an architectural wonder to behold. It used to be located at the corner of Pedder Street and Connaught Road Central. But it had to be surrendered to make way for building the Central Station of the Mass Transit Railway. Its replacement was externally not half as pleasing on the eye but it did come with a very spacious and up-to-date sorting office in the basement.

At the time I joined the department, there was a staff of approximately 5,000. Apart from the concentration at the General Post Office, they were scattered among 40 branch post offices around the colony. The oldest branch was at Stanley, opened in 1937. That branch is still operating today in its original building. The number of branches has since climbed, to approximately 130 I think, including the odd two or three mobile ones.

The departmental structure was then quite a simple affair. There were beneath the Postmaster General and his Deputy two expatriate Assistant Postmasters General, one to head postal services and the other the telecommunications side. Most of the staff worked on the postal side. The telecommunications side was made up of technical staff who oversaw the two franchises granted for local and overseas telecommunications services respectively.

The local telephone franchise, valid until 1995, was held by the Hong Kong Telephone Company. The company was restricted to an annual return of 16% of shareholders’ funds.

The overseas telephone franchise was granted to a Hong Kong subsidiary of Cable & Wireless. The parent company had its origins in a British company set up in the 1860s to provide cable links to various parts of the British Empire. With the steady rise of wireless communications, the different communication methods were merged into a single company in 1934, known as Cable and Wireless Limited.

Following the Labour Party’s victory in the 1945 general election in the United Kingdom, the company was nationalised. Its domestic telecommunications monopoly was passed to the British Post Office while it continued to operate telecommunications services outside of Britain. One of its subsidiaries held a franchise for Hong Kong in return for a two percent royalty on turnover.

For some unclear reason, no profit limitation clause had been included in that franchise. That sometimes led to unseemly results. For instance, in 1992 the company made an annual profit of HK$5.6 billion on shareholders’ fund of HK$12.2 billion — a whopping 47% annual return on capital. A veritable wet dream for a monopoly, even by the colony’s freewheeling standards!

An announcement at the end of 1979 of my projected arrival in the new year as the Deputy Postmaster General caused a minor stir among the staff. They did not know exactly what to expect. I was not only an outsider but I would be the first Chinese to hold a top post in the department. The Postmaster General was on his last tour before retiring in January of 1982, so he was in a relaxed and happy-go-lucky mood. He was more than willing to give me my head. My priority was, naturally, to defuse the threat of another postal strike.

* * *

Staff and management relations within the department were not particularly harmonious. Otherwise there would not have been issues leading to repeated strikes.

I found that the administrative and clerical back-up for running such a large department was somewhat inadequate. So I requested the Secretariat to assign a Senior Executive Officer by the name of Wong Yiu-Wing to take over as the new Departmental Secretary. I had worked with Yiu-Wing in the Home Affairs Department before and had found him a highly efficient and capable officer. My request was quickly met and Yiu-Wing lived up to his record for sound bureaucratic reconstructive surgery.

Then it came down to familiarising myself with the large number of trade unions and staff associations within the department and to getting a feel of the personalities of their office bearers. The grades in the department ranged from the lowly postmen on the beat to clerical staff, manual labourers, night watchmen, Postal Officers, Controllers of Posts and telecommunications engineers and technicians. The interests of one group did not necessarily coincide with those of another.

The established way for the management to communicate with staff unions was to hold, from time to time, a general meeting wherein employment issues could be aired and thrashed out. That general meeting was called the Forum and all staff groups were represented. For practical reasons, based on the number of postal staff unions involved, the Forum was chaired by the Assistant Postmaster General in charge of postal services.

It was an unsatisfactory system because the chairman, being an expatriate, knew no Chinese whereas many union representatives of the lower grades knew only enough English to read the addresses on letters and other postal items. That meant that all discussions had to be laboriously filtered through an interpreter. That process provided ample scope for misunderstandings.

Furthermore, many of the issues raised appeared to be of a micro nature, like shift work, promotion prospects, the maximum weight of any mail bag being carried by a postman, the varying lengths of delivery beats, and so forth. A majority of those should have been resolved at a much lower level. To bring such matters before a large formal meeting took up too much of everybody’s time. It also encouraged a “me too” attitude whereby a concession granted to one union engendered a similar demand from another.

After my arrival, I decided to take over the chairmanship of the Forum. I told the Forum that since Chinese had been declared an official language back in 1972 and since everybody except the Assistant Postmaster General spoke Chinese, proceedings would henceforth be conducted in Chinese. The interpreter would be retained to explain proceedings to the Assistant Postmaster General.

I further suggested that the Forum should be used for discussing major structural or career issues; minor tweaking of working conditions could more easily be settled in face-to-face meetings with representatives of the particular union concerned. The door to my office was always open and I hoped union representatives would make use of that facility. It was unnecessary to involve all unions in every discussion.

The pressing issue for the public, I emphasised, was the threat of another postal strike. There might well be certain disparities between the salary scales and promotion prospects for some postal workers, compared with those in other grades in government service. But management could not conduct talks under duress. The sooner union officials explained their dissatisfactions to me, without any threat of a strike, the sooner disparities could be examined and dealt with.

The union officials, after due deliberations among themselves, sensibly accepted my invitation. They called in separate contingents at my office. It transpired that there were indeed certain anomalies. The two sides worked through them, identified the ones enjoying mutual support, and made proposals for changes to the administration. The proposals were then left to work their way through the central bureaucracy.

* * *

Meanwhile, on the personal level, government approval for my premature retirement came through, setting off my required year of notice. The moment the approval was received, I sent in a further application for permission to take up employment with Li & Fung without any cooling-off period, arguing that overseeing postal services could have no bearing upon the core business activities of Li & Fung.

That second application was also duly approved. But then I sent in a third application to tidy up a technical detail. I would have, at the end of my year’s notice, an accumulated leave balance of six months. From the time I stopped working till the end of my leave, I would still be technically in the employ of government and hence be entitled to the usual fringe benefits, like subsidised and furnished quarters.

But a “serving” officer could not take up employment in the private sector without permission. I wanted to start immediately with Li & Fung, without having to sit on my hands for six months waiting for my pre-retirement leave to expire. The money involved was, of course, a consideration. By working right away, I would be able to draw on both my full civil service salary and my Li & Fung pay at the same time. So I applied for permission to work in the private sector while on pre-retirement leave. That too was duly approved.

However, there was yet another bureaucratic procedure I had to comply with. It involved a once-in-a-lifetime decision on whether I wished to commute a part of my pension into a lump sum payment.

At the time I began contemplating retirement, the customary retirement age was 55 and an officer could opt for early retirement at the age of 50. A pensioner would also be entitled to convert up to 25% of his pension into a lump sum payment. The theory behind it was to give him some flexibility transiting from work into retirement. He might, for example, wish to migrate elsewhere, purchase a home, fund an overseas education of a child or grandchild, etc., for which a lump sum would come in very handy.

Any commutation would be based on an actuarial calculation that a pensioner would, on average, live to collect his pension for — if I can remember correctly — something like 14.2 years. A pensioner would naturally have to take his own health prospects and expectation of life into account. If he figured he could only live for a couple of years after retirement, then it would make sense to take the bird in hand.

Just before I was due to make my election, however, one of the factors in the calculation was changed. Instead of being allowed to commute up to 25%, a pensioner was permitted to commute up to 50%.

I believe the pressure for that change came from expatriate civil servants. They had made representations to London to guarantee their pensions in the event the colony could no longer meet its obligations after sovereignty had been reverted to China in 1997. They had been spooked by the deluded Whitehall belief that the place would fall apart at the seams both economically and commercially without British management.

London was thus caught up in the illogicality of its own presumptions. But the domestic calls on the British exchequer were many and it was reluctant to act as a guarantor for the pensions of ex-colonial civil servants. A compromise was eventually arrived at whereby a pensioner could commute up to 50% of pension as a lump sum.

That decision was, in my view, ill-advised and selfish, catering to a sectarian need without being mindful of its psychological effects on the general public confidence during a delicate time of transition.

I had not the slightest doubt that Hong Kong would continue to thrive and prosper, with or without the British. If it had not been for the need for ready money to send my two younger sons overseas, I would not have commuted any part of my pension. In the circumstances, I commuted only 25% of my pension and I have regretted it ever since.

Today, 37 years after my retirement, I am still drawing a Hong Kong pension and paying Hong Kong taxes. But I still have a long way to go to beat my grandfather’s record of drawing a Crown pension for 41 years!

Since my retirement, the rules have been changed again and again. I believe the current retirement age is 65. I have no idea what the current commutation factors might be.

* * *

On the staff relations front, the proposed changes in the terms of service for postal workers were fairly swiftly agreed by the administration and the threatened postal strike was averted.

After the dust had settled, Sir Jack Cater, the then Chief Secretary, sent me a message, congratulating me on defusing the strike threat and asking if I would consider withdrawing my application for early retirement. He said the government could hardly afford to lose a senior officer like myself.

My reply was that I was in a financial bind. All my three sons wanted to study in North America and, much as I would like to remain in the public service, its salary structure would not enable me to meet the wishes of my sons. Even if I were to be promoted immediately to the rank of Policy Secretary, my salary would still fall far short of financing requirement. Hence I had no alternative except to leave for the richer pastures of the private sector.

There the matter reached a dead end.

* * *

The months of my retirement notice rolled by quickly enough. My involvement with staff unions and reorganising the administrative machinery of the department kept me busy.

Over the same period, I had several sessions with Victor Fung to fill in the details of my terms of engagement with Li & Fung.

By the time autumn came around, it was time for the Postmaster General to take his annual leave. I was slated to take over as Postmaster General, in addition to my duties as Deputy. Before departing, the head of department handed me the keys to the Chubb safe in his office and said: “Since you will be in charge of the department, you might as well look at some of the secret papers in the safe.”

I accepted the keys. But I thought he was referring to papers detailing what everybody had long talked about in the tea houses and coffee shops, that is, of the British GCHQ or Government Communications Headquarters, in cahoots with the Americans, setting up surveillance posts at such places as Cape Collinson and Lei Yue Mun to spy on Chinese telecommunications.

I accepted the keys. But I thought he was referring to papers detailing what everybody had long talked about in the tea houses and coffee shops, that is, of the British GCHQ or Government Communications Headquarters, in cahoots with the Americans, setting up surveillance posts at such places as Cape Collinson and Lei Yue Mun to spy on Chinese telecommunications.

Once I got around to opening the safe, however, I found myself proved entirely wrong. It became apparent that another well-established surveillance operation by the Special Branch was being conducted right under my nose in the General Post Office as well! So much for my blind faith over most of my life in the sanctity of the Royal Mail.

How could I have missed what was going on? It was true that doing my rounds of inspection in the basement I had neglected to go into every office there. I had been more interested in the workings of the modern sorting machinery and how individual postmen would bundle their letters and postal items in accordance with the routes they took on their delivery beats.

And it was in one of those inconspicuous rooms in the basement, during the dead of night, that certain postal officers specially selected by the Special Branch would steam open letters addressed to targeted individuals and photograph their contents, before re-sealing them for normal delivery the following day.

The whole operation revolved around a list of names and addresses drawn up by the Special Branch. For some unclear reason, the list was referred to as “The Q List”. I could not figure out what the cryptic “Q” was supposed to stand for. Presumably it might stand for “Queer” or “Questionable” or “Quisling” or something of that nature.

The list was delivered personally to the Postmaster General from time to time, whereupon he would instruct the specified postal officers pre-selected by the Special Branch to photograph all communications passing through the postal system destined for those particular people or addresses. It required no imagination to conclude that a similar secret list would have been sent to the head of the Hong Kong Telephone Company, for all telephones either in the names of those people or located at those addresses to be bugged as well.

On the face of it, it appeared that the people in the Q List had been selected for either political or criminal reasons, though some element of collecting economic intelligence might be present as well. Most of the names were unknown to me, although a few could be identified as minor personages belonging to the cocktail cult, the odd banker, lawyer, accountant or businessman. Thankfully, no name of any close friend of mine had found its way into the list.

A feature of the list was that where the address happened to be a self-contained dwelling rather than an apartment, then the name of the target was not specified. Instead, all communications going to those addresses, under whatever name, would be intercepted and photographed.

Nonetheless, one of the addresses I came across gave me both a start and a chuckle. It brought to mind some of the stories of past bungles I had heard concerning the Special Branch. Those relating to the Vietnamese revolutionary hero and statesman, Ho Chi-Minh, were particularly memorable. That wily revolutionary had repeatedly led Hong Kong Special Branch operatives on a merry dance as he skipped in and out of the colony using multiple aliases. Once he even faked his own death while hospitalised, leading the Special Branch to close his file and to report his demise to other spy agencies.

My own limited encounters with the Special Branch did not alter my opinion of its general ineptitude. Included in the Q List was an address in Victoria Road with which I had some familiarity. Its inclusion convinced me it had to be yet another Special Branch faux pas.

The address in question had been included probably because it happened to be the putative home of Fok Ying-Tung, the Hong Kong multi-billionaire businessman, philanthropist and highly-regarded advisor to the Chinese government on Hong Kong affairs. The irony of the situation was that Fok could hardly ever be found there.

My familiarity with the address had nothing to do with Fok himself but rather with a couple of other members of his family. When I visited the Hong Kong Chinese General Chamber of Commerce club regularly to play mah-jong with friends, I sometimes bumped into Fok. His presence there was unremarkable for he was one of its most important personages. But we would merely exchange nods in greeting, without ever engaging in conversation.

Fok was born in 1923 in Poon Yu, where his family had a small boating business. His father was killed in an accident when he was about eight. He went to school in Hong Kong, but dropped out before finishing secondary school due to the outbreak of war with the Japanese. He then began working as a labourer.

When the Korean War broke out, the United Nations imposed an embargo on trade with China. Fok was among other patriotic Chinese in Hong Kong who set about breaking that embargo by smuggling vital supplies like medicine and machinery to China to support its war effort. Afterwards, as a reward for his risky services, Fok was granted a monopoly for exporting sand to Hong Kong. Since sand was a vital component in building construction and the colony was going through successive building booms, it took no time for Fok to make his fortune.

He then expanded into hotels, real estate, petroleum and casinos in Macau. His links with the highest levels of the Chinese government flourished apace. The Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang, for example, recorded in his secret journal Prisoner of the State discussions he held with Fok about developments in Hong Kong.

Fok was thus soon made a member of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and a Vice-Chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

In Hong Kong itself, Fok’s standing also rapidly grew. He came to prominence particularly as the “white knight” who rescued a crumbling shipping empire.

During the heyday of the shipping boom of the 1970s, there used to be three shipping titans operating out of Hong Kong — the Pao family, the Chao family and the Tung family. Big money could be made or lost based on an operator’s assessment of freight rates and hull values. The Tung family, operating as Orient Overseas under C.Y. Tung, the father of the first Hong Kong post-colonial Chief Executive, C.H. Tung, made the wrong forecasts and was soon in dire financial trouble. It was at that point that Fok entered the picture and saved Orient Overseas from bankruptcy.

In 1984, Fok established the Fok Ying-Tung Foundation to promote education, health, sports and science and it became the largest philanthropic organisation in the city. He became President of the Hong Kong Chinese General Chamber of Commerce from 1984 to 1988 and then again from 1990 to 1994. He was also President of the Real Estate Developers Association of Hong Kong and — because of his passion for soccer — President of the Hong Kong Football Association.

He passed away in 2006, from cancer, leaving three wives and 13 children.

* * *

My familiarity with the Victoria Road address stemmed from my friendship with Fok’s eldest daughter, Patricia or Lai-Ping. I had met her in the 1960s, when she was working on an album of photographs which came to be titled Hong Kong Through the Looking Glass.

Pat was a superb photographer with a genuine passion for her work. She had studied in England, Switzerland and the United States and had taken courses in design and the photographic arts. Afterwards she was forever clicking her Hasselblad wherever she went.

We shared a strong attachment to China and its history and culture. Pat always had some excitingly ambitious project in China under consideration. It might be retracing the steps of the Tang poet, Li Po, climbing the Yellow Mountain and trying to recapture, through photographs, what the poet might have seen along the way. Or else Pat would head off to Tibet to give photographic substance to what an ancient Tibetan poem had described as “the centre of heaven, the core of earth, the heart of the world fenced around with snow.”

Many parts of China had been still closed to outsiders at that time but Pat somehow always managed to use her father’s connections to gain access to wherever she wanted to go. The result was two further fine albums — one in 1974 entitled Faces of China and the other in 1987 entitled Quiet Beauty of China.

I greatly envied Pat’s ability to roam all over China. Ever since I had been denied permission by the colonial administration to visit Taiwan, I saw no hope of my being allowed to go to China so long as I remained in Crown service. I therefore derived vicarious pleasure in listening to Pat’s accounts of the historical and scenic places she had photographed or visited. Whenever she was passing through Hong Kong I would grab the opportunity of having a cup of tea or a meal with her. Pat had, in the meantime, married a Dutch businessman and they had set up home in London, in a town house in Mayfair. So her visits to the colony became more erratic.

During one of Pat’s stopovers, when I was working in the Home Affairs Department, she introduced me to her mother and asked if I could help her with a problem. Pat’s mother was a lovely lady, a homely Chinese housewife of the old school. She was courteous, soft-spoken and slightly hesitant before outsiders. She came across as very much in the same mould as my beloved Eighth Grandaunt.

It appeared that Pat’s mother had lost one of her more important official documents — a birth certificate or an identity card, I cannot now remember exactly which.

Like most Chinese housewives who had never had dealings with colonial officialdom, she was apprehensive over what might be involved in securing a replacement. She was fearful of having to explain before some haughty and intimidating European how her loss had come about. She herself was unsure of how the document came to be lost and she dreaded being tripped up by questions she could not answer.

I reassured her she had nothing to worry about. I would explain the problem to the department concerned, make an appointment for her to see an appropriate officer and shepherded her through the entire process. Everything went without a hitch. I was more than glad to be of service to so pleasant a member of the public.

* * *

Hong Kong was one of those tight, high-pressured cities sprouting a plethora of overlapping cliques of wealth, snobberies and charlatanism. In what other city in the world could a person find in the early 1970s four stock exchanges operating in fierce competition with one another? Or to find a stock index running up from 150 to 1,775 in a matter of a mere 18 months? Something did not smell right. It was almost inevitable that a few years later the chairman of one of the exchanges by the name of Li Fook-Shiu should be sent to prison for four years for corruption and accepting a reward while he was the chairman of one of the exchanges.

In such an à gogo business environment, anyone participating even marginally in its endless rounds of celebratory dinners and cocktail parties was bound — over time — to rub against the entire cast of colonial characters and hangers-on, ranging from philanthropists and physicians to predators and philistines. And thus it was that I became acquainted with Fok’s second wife — through her unexpected participation in a mah-jong game I had been scheduled to play.

For a number of years, as I had explained in Chapter 4, I had been playing mah-jong regularly at the Chinese General Chamber’s club with a group of close friends. The core of the group consisted of Ip Yeuk-Lam, a long-standing Vice-President of the General Chamber, Lo Yuk-Chuen, a jolly retired banker, referred to affectionately as Sixth Eldest Brother, H. T. Liu, a shipping magnate from Shanghai, addressed normally simply as Uncle Lau, and myself. We all commanded roughly the same level of game-savvyness and skill. Our challenge lay in how quickly we could suss out one another’s strategies, feints and sucker traps and beating the rest to the punch. It was well known within the club that we did not welcome outsiders to our game, unless we happened to be one player short.

Yeuk-Lam was the one among us who had the most social and official engagements. So it was left to him to initiate a game whenever he had a free evening. He would do this through a staff member at the club, who acted as an informal convener, ringing around to form our ideal table. Sixth Eldest Brother, being a gentleman of leisure, was always available. Both Uncle Lau and I were equally keen to participate, unless one of us happened to be out of town or otherwise engaged.

The Chinese General Chamber was also a natural stamping ground for Fok because of his prominent business and political roles, though he was not a mah-jong enthusiast. He sometimes brought his second wife to the more ceremonial functions at the chamber. Why it should have been the second wife I did not know. Perhaps it was not even his choice.

The second Mrs. Fok soon began using the chamber club to entertain her own friends. In that way she came to know of the regular mah-jong games that Yeuk-Lam had set up for our selected group. She made it known she wished to join our game.

None of us was enthusiastic about any outsider butting in, let alone a woman. It was also not normal in Chinese etiquette for a woman to be playing mah-jong at a public venue with a group of men. Perhaps she merely wanted to establish her own standing among such influential old guards at the General Chamber like Yeuk-Lam. No one was sure of her real motives. But what we were all adamant upon was that we did not relish a feminine presence to cramp our style. We were sometimes given to using unparliamentary language when we got outfoxed by one of our group. Such language could hardly be escaping our lips if there was a woman present. The informal convener was thus instructed to come up with some creative untruths to explain his failures to fit her into our game.

But the second Mrs. Fok was a pushy woman, one not easily deterred. She would go directly to Yeuk-Lam to ask if he might persuade one of the players to give up his place for her, on the excuse she was at a loose end and itching for a game.

Now Yeuk-Lam was not only a consummate diplomat, but also someone brought up in the old school of Chinese social intercourse, never to make anyone lose face, especially the wife of so important a member. Yeuk-Lam would then contact Sixth Eldest Brother, an old friend of many decades, to explain his dilemma. Predictably, Sixth Eldest Brother, being the most obliging of gentlemen and a long-time friend, would gracefully indicate he had been thinking it was time for him to spend an evening with his collection of antique watches in any case.

It was under those circumstances that I found myself one evening sitting down to a mah-jong game with Mrs. Fok. The pleasure of the evening was decidedly not mine, for Mrs. Fok was not only a sub-standard player but one prone to talking far too much. After a second occasion when I found myself unexpectedly in a game with Mrs. Fok, I told the informal convener that in future I would be delighted to surrender my place at the table if Mrs. Fok wanted to play. After that, I never played with her again.

* * *

After I had become aware of the Q List, it struck me as ludicrous that the private correspondence and telephone calls of so many inhabitants at the Victoria Road address should be interfered with just for the sake of keeping tabs on Fok Ying-Tung’s political or other activities. The whole operation was like episodes from one of those old Laurel and Hardy slapsticks — immensely amusing and full of comical mistakes hardly plausible in real life. How could any useful information be gained through such a clumsy and cockeyed operation?

For a start, the house at Mount Kellett Road, where the second Mrs. Fok resided, had not been included in the Q List. I did not know where Fok’s third wife was located but I could not spot any likely address in the list either. What about Fok’s various business offices and charities? Or his regular hangouts like the Chinese General Chamber? Besides, Fok himself was constantly on the move, in China and elsewhere.

I suppose the leading lights in the Special Branch, being all expatriates, would not know much about the psychology and ingenuity required of a man who has taken on three wives. Poor fellows! How could they know that by the time a man had acquired a third wife he was unlikely to be spending much time in tête-à-têtes with his first wife? Having lived with a polygamous grandfather during my boyhood, I had at least learnt that much about human nature!

If the Special Branch were trying to get its hands on, say, the minutes of meetings Fok had attended in the Chinese capital, would those not be delivered by secure courier rather than through the ordinary postal system? There had to be easier ways of finding out. What about by simply asking the man himself? By all accounts of those who knew Fok well, he was said to be quite a straightforward and decent man, with the interest of both Hong Kong and China at heart. If the Chief Secretary were to invite him to lunch at Victoria House or the Governor at Government House, who could say what useful information might be exchanged after tongues had been lubricated by a few shots of pre-prandial sherry. Or was Fok too much of a persona non grata for making such a mockery of a United Nations embargo and got off scot-free?

The world would never know what inconvenient truths might have surfaced if one of the parties had dared to initiate a conversation outside the confines of staid protocol.

And what if the Special Branch’s surveillance of Fok had stumbled upon some wrong-doing or indiscretion by another member of one of his households? Would the information be filed away somewhere for later use against the person concerned? Or used as blackmail against the principal target? Would such shady ramifications be legal?

There was no documentation in the Postmaster General’s safe which definitively addressed those questions. However, since the operation had been running for a goodly period, the issues of legality and public interest must have been already weighed carefully by the administration’s legal and constitutional advisors.

All colonial regimes came fully equipped with draconian internal security regulations in case of mutiny or rebellion. Hong Kong was no exception. Regrettably, far too many ex-British colonies had retained those harsh British laws after independence to keep their populations under control. British politicians frequently boasted of establishing the rule of law in far flung places but none seemed willing to praise the internal security laws they had bequeathed as well. Thinking about such issues, however, soon led me inevitably into the toxic fog rising out of yet another bureaucratic moral swamp.

In an open and accountable society, the privacy of its citizens should matter greatly and should not be invaded by third parties without judicial due process. Such intrusions could hardly be justified on the flimsy grounds of fighting crime or national security alone. If that was the case, then how should the claims of friendship stack up against the requirements of public duties? Should I reveal to Pat and her mother, for instance, that their letters and phone conversations were being monitored by governmental agencies without their permission?

But before I could work out the right answers, another surprising development set me back on my heels.

* * *

When I took over as Postmaster General, I chose to work from the Deputy’s office using my existing private secretary, rather than to move office and break in a new secretary. The only exception I made was when I had to deal with some of the secret files in the Postmaster General’s safe.

One day, I had gone down to the main hall of the General Post Office on a lower floor of the building to observe the staffing levels at the various postal counters and to determine how quickly customers were being served at each. After a while, I headed back to my office.

On the way back, I saw a couple of postal officers emerging from the ante-room to the Postmaster General’s office. As we approached one another along the corridor, I asked if they had wanted to see me.

“No, Sir,” they replied, rather sheepishly, before continuing on their way.

After they had disappeared from sight, I was tickled by a slight curiosity. I headed for the ante-room, where the Postmaster General’s private secretary was located, and asked her what the two officers were after in her room.

“Oh, they were just collecting their pay, Sir,” she replied.

“Their pay?” I said, puzzled. “But the Treasury pays all of us directly through bank accounts.”

“It’s for their night shifts, Sir.”

“But officers on shifts get paid the same way. Why would they need to come here?”

“They’re the people doing unofficial overtime, in connection with the Q List. Their overtime is paid in cash. I’ve been asked to handle those payments and I, too, get paid extra for that work. Our understanding was that the extra money need not be declared for tax purposes.”

“Oh, yes, of course. Slipped my mind completely,” I said, shaken, before retreating quickly to my own office.

* * *

Back at my own desk, I was astounded by my latest discovery. I had deliberately refrained from asking the Postmaster General’s secretary further questions for fear of exposing my own ignorance and of finding more unsavoury surprises. Internal security regulations might put a legal veneer over rifling through people’s mail and tapping their phones for the sake of fighting crime or protecting national security but I could not imagine how using some slush fund to fiddle on income tax could be justified.

The government had trumpeted the setting up of an Independent Commission Against Corruption to fight corruption in society and yet it was using improper practices to circumvent the law within its own administration. And here I was, unwittingly supervising a part of that malpractice. How could I keep silent and do nothing?

But all the courses of action open to me seemed completely useless, if not actually dangerous. I could, for example, pretend to be upset and demand to know why my staff involved in operating the Q List were getting extra tax-free cash whereas I, as their head, was getting nothing. The trouble with that approach was that the next time the moneybag came around there might well be a sum earmarked for me! That would suck me deeper into the morass.

Any other form of protest would appear just as pointless. I was a bird of passage, holding the fort only temporarily, waiting for the substantive head of department to return from leave. Any protest I made could easily be put in a government pigeon-hole until after my retirement. That would render the entire matter irrelevant and moot.

I could possibly inform the Commissioner for Inland Revenue that I suspected some of my staff were not declaring all their income for salary tax purposes. But that would only land the staff involved in hot water. They were only doing what they had been told to do, as expendable pawns in a cynical game played by foreign puppet masters. Putting them on the spot would not resolve the inherent contradictions in the system.

Whistleblowing to some of my old journalistic friends was another option. But it would not take the administration long to zero in on the source of that type of security breach. I was bound by the provisions of the Colonial Regulations as well as the Official Secrets Act. The dreaded Colonial Regulation 55 could see me out on the street without a pension and without a recourse. Under the Official Secrets Act I could be prosecuted and imprisoned. What would happen to my children and their education then? I was almost home and dry, with a well-paid job and pension waiting for me. Was it worth risking all that on a vainglorious matter of principle?

I mulled my dilemma longer and more searchingly than I really needed to. That delay conveniently brought the Postmaster General back from leave. The issue of principle was now clearly his to ponder rather than mine. Truly Shakespeare had it right all along. Conscience doth make cowards of us all.

* * *

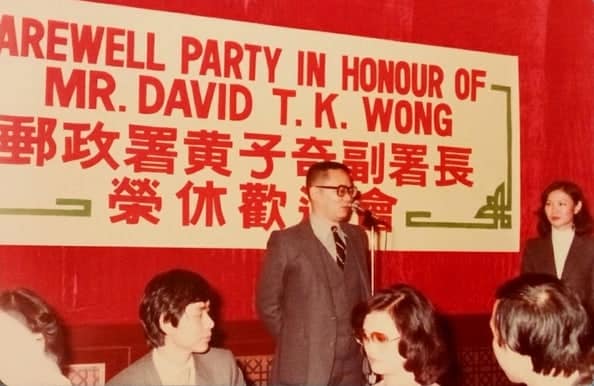

With the return of the head of department, the time had arrived for me to leave. I was much humbled and moved by an initiative by the staff of the department to give me a farewell dinner. I was an outsider and not really one of them. I had been in the department for only a year and had actually met only a small number of the 5,000 or so. I felt deeply touched.

In truth, I had done very little for them. I had merely simplified and improved the means of communication between staff and management. Perhaps I had boosted the confidence of the Chinese staff a little, by demonstrating that they could function with equal efficiency without being led by expatriates at the top.

The staff, after discovering my interest in antique Chinese seals, also clubbed together to present me with a beautiful and costly piece of seal stone known among connoisseurs as a “white hibiscus”. I naturally sought the government’s permission before accepting so fine a gift.

All in all, I left the department with a certain amount of regret. If circumstances had been different, I think I would have enjoyed staying longer in that department. But that was not to be.

* * *

Footnote:

In 1982, a little over a year after I had left the department, one of the postal unions went public with a complaint of discrimination. It alleged that while certain of its members were allowed to earn extra money by working overtime on night shifts, other members were not granted that same opportunity.

The response from the government was that the anomaly had been remedied. It scrapped the entire Q List operation altogether, obviating the need for Special Branch approved postal officers to perform the clandestine work. The swiftness with which the long-running scheme had been done away with suggested that it had probably been neither effective, efficient nor necessary to begin with. The whole matter thereby petered out without public fuss.

Once again, the editors and investigative journalists of the supposedly free press had apparently been fast asleep on their jobs. No one contacted the trade union in question to discover the nature and roots of its complaint. Neither did anyone probe the administration to explain the allegation of discrimination.

If somebody had, there might well have been quite an interesting story about just how much public money the government had been spending to photograph the letters of ordinary citizens and to tap their telephones to allegedly prevent crime and subversion. The results, presumably, could or could not be shown to justify the cost and effort. Either way, some additional public relations spin would have been required. If the results were meagre or questionable, why had the operation been going on for so many years? And if good results spoke for themselves, why suspend the operation?

The episode illustrated clearly why a free and independent press has to be vital to the health of any free and democratic society. The Fourth Estate has the responsibility to record, elucidate, educate and entertain, while at the same time holding governments and big public entities to account. This was of particular importance in a society driven by naked free market capitalism at one end and a cosy collection of franchised monopolies at the other. Without active and enquiring journalism, society would soon degenerate into a playing field for the rich and the powerful.

That role for the media is given added importance in the present age of general governmental incompetence, propaganda, bluster, disinformation, lies and deceit. The privacy, liberty and even lives of ordinary citizens are being sacrificed too often — possibly even willingly so — in order to protect society from some mocked-up or exaggerated evil. There needs to be openness and accountability for many of the deeds done by governments in the name of their citizens. Both independent media and whistleblowers have vital roles to play.

Recent events have shown how the mainstream media in many parts of the world, in a greedy search for quick profits, have descended into sheer gutter journalism. The American mainstream media, for example, are controlled by a group of five or six conglomerates and through their bad handling of the 2016 presidential elections, had produced the unintended consequence of having Donald Trump elected to the most powerful public office in the world. They seemed to have sunk even further below the abominable “yellow journalism” standards set in the era of William Randolph Hearst.

In journalism — as in other important fields of social endeavour like banking, the judiciary and government — public trust is of the utmost importance. Once that has been compromised or lost, the public would cease reading, listening or viewing what they have to offer.

Concerned citizens should, however, also be aware that people usually end up with the media they deserved. The advances in technology, the rising costs of production and the relentless concentration of media power in the hands of a few gigantic corporations are posing serious challenges to independent voices in the media in all democratic societies.

Just within my own lifetime, I had witnessed in Hong Kong the disappearances of two venerable newspapers due to the ravages of market forces — the China Mail and the Hong Kong Telegraph. The former had existed for 130 years and I had been accredited as its London correspondent for a year during 1957-58. So its demise in 1974 created quite some nostalgia and regret for me.

Ultimately, it is for ordinary citizens to decide what they want as their source for news, information and analysis. If they do not want to put up with a numbing diet of empty slogans, fake news, official handouts and celebrity tittle-tattle then they have to do something about it. Unfortunately, there is no such thing as a free lunch. If they want something with substance, something which would enhance their daily lives, then they will have to pay for it.

Read more of Wong’s memoir here.

Leave A Comment